Christianity, Conservatism, and Nihilism

Growing up in the American evangelical movement, I was warned countless times, sometimes with warnings of fire and brimstone, but more often in ways more subtle and convincing than words, that belief in God was the cornerstone holding the universe together. The world without God is empty, frail, and poor, we would sing, and without God’s constant outpouring of renewal into his creation, everything would immediately start to decay. And indeed, when I lost my faith at fourteen, I found it to be true: I experienced the world as a degenerate, cold, purposeless, and unredeemed place, which lacked even the capacity for redemption. But the fact that the prophecy came true, self-fulfilling thought it was in retrospect, didn’t actually help me regain my faith. Because conviction, whether we possess it or lack it, is that part of us which cannot submit to what is desirable or beneficial. Long after my faith had died, I would have given anything to believe in an all loving and all powerful God, to put an end to the torment I inflicted on myself and the bitterness I harbored against a god I didn’t even believe in. But my unfaith would not yield to what I so desperately wanted to be true. No wishing or pleading could erase the simple truth carved into on my heart:

Rain falls on the good and the bad alike. An unjust world cannot be the product of an all-loving and all-powerful God. He is either indifferent to human affairs, or he does not exist.

What I came to realize, however, was that the picture I had of a cold, mechanical world, hopelessly broken without a rational creator was only the opposite of belief in God as one side of a coin is opposite the other. In both cases, life is challenged by a standard from outside, a standard it can’t help but fall short of. In the case of belief, despite the impossibility of life attaining perfection, an inner peace is possible because you feel the rightful judgment has been somehow withheld, the execution stayed. With unbelief, this peace is impossible, and you feel an intolerable unrest in readiness of a judgment which must come sooner or later, a debt which you cannot hope to repay. In both cases, infinite debt and infinite guilt are assumed. It was only when I began to challenge the subconscious sense of the infinite debt that I could begin to imagine a world which is self-creating, neither inherently guilty nor entirely innocent, a world of infinite spontaneity, creativity, renewal, and play; in short, a world I would actually want to be a part of. While the insight about the world that first came into conflict with my faith has never wavered, I no longer experience my lack of belief in the infinite debt as a loss. On the contrary, I’ve exchanged a world of certainty and bondage for one of contingency and freedom. While I experience my share of fear and trembling, this is the price of freedom, and I wouldn’t want to be entirely rid of it, given what I’ve seen people are capable of when they feel god is on their side.

Nevertheless, all is not well. It is difficult to escape the feeling that something has gone horribly wrong. The modern world seems caught up in an unstoppable acceleration which goes beyond the power of individuals and governments to understand or control. We feel confused, exhausted, and everything stable and familiar seems to constantly fall out from under us. Despite an unprecedented increase in total wealth, we find ourselves unable to allocate said wealth and knowledge to solve cooperative action problems, an inability which might kill us much sooner than we imagine. Many young people report a feeling of unreality, become jaded and cynical at a shockingly young age, and the norm of our time is to hold the world at ironic distance.

Self-described conservatives in the public sphere have a name for this condition: nihilism. You can find countless examples of conservative figures in media decrying the hedonism and nihilism of modern societies, recommending (when they do anything beyond complain and mock) that we return to “traditional values”, belief in god, or somesuch. The implicit world picture is always the same: we have forgotten the infinite debt. Confusion and decay are the price.

Unfortunately, even if I thought it would be desirable to take up the old yoke, the path to salvation recommended by postmodern conservatives like Jordan Peterson can never work. You can’t make yourself believe in something because you’re afraid of what will happen if you don’t. All you can do is add one more crime to the infinite list: I ought believe, but my heart convicts me that I do not. I can think of nothing more nihilistic than spending your life telling others to believe, or at least act as if they believe, something from which honesty demands you withhold your assent. In the words of Martin Heidegger, an atheist with all the fear and trembling of the devout:

Only a god can still save us. I think the only possibility of salvation left to us is to prepare readiness, through thinking and poetry, for the appearance of the god or for the absence of the god during the decline; so that we do not, simply put, die meaningless deaths, but that when we decline, we decline in the face of the absent god.cite

In other words, even if you believe a world without God is intolerable and unsustainable, better to decline in truth than prosper in a lie. The conditions of modernity have conspired to make it so no one who is dependent on modern societies for their survival can totally escape the dangerous spirit of questioning. In order to resolve this anxiety, conservatives finds scapegoats: “it is not you who feels uncertain in the face of an overwhelming torrent of possible beliefs about the world, it is Critical Race Theorists, Post-Modern Neo-Marxists, and Gender Ideologues who are producing dangerous, motivated ideas to attack and pervert your self-evident and eternal way of seeing the world. It is not that your beliefs are difficult to maintain in a world of instantaneous communication and the unprecedented advancement of the natural sciences; the problem is that they are under attack by people who are not fighting fair, people who fear and resent your beliefs.”

But there is something fishy about this narrative. If the scapegoating accounts of nihilism in conservative media were right, conservatives would have nothing to fear from progressives; after all, they have meaning and purpose, founded in self evident and unshakable faith; what could godless, decadent liberals offer to compete with such assurance? Why do children need to be protected, through censorship and withdrawal from public life, from ideas which are so obviously empty and unsatisfying? And yet churches, along with every other institution of collective life, continue to hemorrhage membership. Those that remain resort to increasingly illiberal means to maintain themselves and their children in their beliefs, and become increasingly violent towards anyone who threatens to expose them to alternatives. Just as something feels unmistakably weak and unmanly about someone who constantly talks about masculinity, the conservative fixation on nihilism carries a whiff of confession.

Here again we find in liberals and conservatives two sides of one underlying tendency. Both cannot help but feel an uneasiness that something has gone horribly wrong. Conservatives find easy scapegoats; liberals condemn the easy scapegoating, with the implicit message that nothing is fundamentally wrong with liberal capitalism; we just have to work out a few remaining bugs, racism, sexism, and so on, by calling out prejudice when we see it. We don’t have to fall into this trap. The truth is that there is an ongoing crisis in modernity, a crisis which no one has been able to once and for all surmount. While the problem goes beyond any single human will or endeavor, within it, many have lived beautiful lives, made magnificent works, and deepened the hues of the problem, precisely by refusing to displace it onto easy scapegoats. To be anti-nihilist requires precisely one confront the problem of modernity, soberly, in all its indominable sublimity, rather than clinging to the undead remains of comforting illusions that have served humanity for so long.

With that in mind, I’d like to trace the contours of the crisis of meaning, through the lens of of how American Evangelicals, Conservatives, and the various currents that mix therein talk about it. My only aim is to get you to set your sights a little higher, or a little lower, than what “the other side” is doing; to see how both are symptoms of an inhuman process, far beyond mere morality.

Meaning and Purpose⌗

“What is the meaning of life?” seems at first glance like a simple question, which any philosopher worth their salt ought to be able to answer. But the question itself neatly hides all sorts of metaphysical assumptions which have to be first unpacked before it can even be posed. “Meaning” is a feature of language; words are generally understood to refer to something which exists in this place we call reality. For example, tree refers to the set of objects which have roots, hard bark-covered trunks, branches, and leaves. Even when words refer to something abstract, like countries or political ideologies, they are assumed to relate to something outside of language, which has a more important sort of reality than the word used to designate it. But to ask the meaning of life is to reverse this assumption; it is to assume that life, the ground of our intelligible reality, refers to something linguistic. This assumption might be true; it may be, as Jordan Peterson and many Christians believe, that what happens in physical reality is an effect of something nonphysical happening elsewhere, in a immaterial, meaningful realm. But the assumption in the question decides everything important about the answer; by the time one asks what the meaning of life is, it is already decided that what happens in reality is a mere reflection of something outside of it.

For now, we can neatly side step the issue of whether essence precedes existence (more on this later) by asking a different question, one which I think most people mean when they ask after life’s meaning: “what is the purpose of life?” This simplifies things somewhat, but as you will see, even this concept is saturated with metaphysical assumptions.

The idea of objects having a purpose seems natural and intuitive. Even without having seen a hammer in use, if you are acquainted with human bodies and tools, it is possible you might correctly guess the purpose of a hammer is to drive nails. You might assume, once this is demonstrated, that all hammers were created for this purpose. Aristotle went so far as to claim that purpose, or “final cause”, is one of the four causes which every object possesses which together bring it into beingcite. Whether that be a human creating the object for their use, or the gods creating it to serve some function in the harmonious maintenance of the world, all objects are understood to have an intrinsic relation to the uses rational beings may put to them.

It’s impossible to overstate how important the doctrine of final cause has been to western, and Christian, thought. (An aside: most Evangelicals hold to the doctrine of sola scriptura, the belief that the divinely inspired Bible is the sole authoritative text. Unfortunately, the subconscious mind is incapable of submitting to the dictates of doctrine; even if you have only read The Book, you cannot help but absorb ways of thinking which predominate in your social worldnote, and which change through time, influenced by factors exigetical, historical, and material. Hellenism and Judaism, while often spoken of as if they were separate intellectual traditions, developed in dialog with each other throughout the centuries. While one can trace direct influence from Thomas Aquinas and other eleventh century scholars who synthesized Aristotle’s newly rediscovered works with Christianity, through Martin Luther and John Calvin, to any contemporary Protestant sect you choose, this is sort of missing the point. For most people, final cause is not a proposition to be affirmed or rejected, but a preconscious way of seeing the world, partially spontaneous, partially influenced by scholars and theologians, and transmitted socially. Even if you have never read Aristotle, final cause is so deeply ingrained in western ways of thinking that it almost certainly has a greater effect on your everyday life than does, say, your position on transsubstantiation. If Evangelicals consider this problem at all, their counter arguments usually go something like “sorry but I’m built different"note, with all the lacking introspection of those who claim to be unaffected by advertising.) Returning to the topic at hand: why does final cause matter so much? Why is the concept inextricably bound up with the unbearable despair I felt when I lost my faith? To answer this question, I will turn to Spinoza:

…All such opinions spring from the notion commonly entertained, that all things in nature act as men themselves act, namely, with an end in view. It is accepted as certain, that God himself directs all things to a definite goal (for it is said that God made all things for man, and man that he might worship him). I will, therefore, consider this opinion, asking first, why it obtains general credence, and why all men are naturally so prone to adopt it? Secondly, I will point out its falsity; and, lastly, I will show how it has given rise to prejudices about good and bad, right and wrong, praise and blame, order and confusion, beauty and ugliness, and the like. However, this is not the place to deduce these misconceptions from the nature of the human mind: it will be sufficient here, if I assume as a starting point, what ought to be universally admitted, namely, that all men are born ignorant of the causes of things, that all have the desire to seek for what is useful to them, and that they are conscious of such desire. Herefrom it follows, first, that men think themselves free inasmuch as they are conscious of their volitions and desires, and never even dream, in their ignorance, of the causes which have disposed them so to wish and desire. Secondly, that men do all things for an end, namely, for that which is useful to them, and which they seek. Thus it comes to pass that they only look for a knowledge of the final causes of events, and when these are learned, they are content, as having no cause for further doubt. If they cannot learn such causes from external sources, they are compelled to turn to considering themselves, and reflecting what end would have induced them personally to bring about the given event, and thus they necessarily judge other natures by their own. Further, as they find in themselves and outside themselves many means which assist them not a little in the search for what is useful, for instance, eyes for seeing, teeth for chewing, herbs and animals for yielding food, the sun for giving light, the sea for breeding fish, &c., they come to look on the whole of nature as a means for obtaining such conveniences. Now as they are aware, that they found these conveniences and did not make them, they think they have cause for believing, that some other being has made them for their use. As they look upon things as means, they cannot believe them to be self—created; but, judging from the means which they are accustomed to prepare for themselves, they are bound to believe in some ruler or rulers of the universe endowed with human freedom, who have arranged and adapted everything for human use. They are bound to estimate the nature of such rulers (having no information on the subject) in accordance with their own nature, and therefore they assert that the gods ordained everything for the use of man, in order to bind man to themselves and obtain from him the highest honor. Hence also it follows, that everyone thought out for himself, according to his abilities, a different way of worshipping God, so that God might love him more than his fellows, and direct the whole course of nature for the satisfaction of his blind cupidity and insatiable avarice. Thus the prejudice developed into superstition, and took deep root in the human mind; and for this reason everyone strove most zealously to understand and explain the final causes of things; but in their endeavor to show that nature does nothing in vain, i.e. nothing which is useless to man, they only seem to have demonstrated that nature, the gods, and men are all mad together. Consider, I pray you, the result: among the many helps of nature they were bound to find some hindrances, such as storms, earthquakes, diseases, &c.: so they declared that such things happen, because the gods are angry at some wrong done to them by men, or at some fault committed in their worship. Experience day by day protested and showed by infinite examples, that good and evil fortunes fall to the lot of pious and impious alike; still they would not abandon their inveterate prejudice, for it was more easy for them to class such contradictions among other unknown things of whose use they were ignorant, and thus to retain their actual and innate condition of ignorance, than to destroy the whole fabric of their reasoning and start afresh. They therefore laid down as an axiom, that God’s judgments far transcend human understanding. Such a doctrine might well have sufficed to conceal the truth from the human race for all eternity, if mathematics had not furnished another standard of verity in considering solely the essence and properties of figures without regard to their final causes.cite

Spinoza posits a straightforward psychological explanation of how humans come to view the purposes to which rational beings put objects as one of their essential characteristics. Aristotle elevated this spontaneous misconception to a metaphysical law, a law which both Christians and secular westerners inherit, usually without knowing it; so that it makes sense when seeking the nature of any object, let alone life itself, to ask “what is its purpose?” He goes on to suggest God may not impose such a rule on himself or his creation as we, being creatures of purposeful action, project on himnote:

There is no need to show at length, that nature has no particular goal in view, and that final causes are mere human figments…everything in nature proceeds from a sort of necessity, and with the utmost perfection. However, I will add a few remarks, in order to overthrow this doctrine of a final cause utterly. That which is really a cause it considers as an effect, and vice versâ: it makes that which is by nature first to be last, and that which is highest and most perfect to be most imperfect. Passing over the questions of cause and priority as self—evident, it is plain that the effect is most perfect which is produced immediately by God; the effect which requires for its production several intermediate causes is, in that respect, more imperfect. But if those things which were made immediately by God were made to enable him to attain his end, then the things which come after, for the sake of which the first were made, are necessarily the most excellent of all… this doctrine does away with the perfection of God: for, if God acts for an object, he necessarily desires something which he lacks. Certainly, theologians and metaphysicians draw a distinction between the object of want and the object of assimilation; still they confess that God made all things for the sake of himself, not for the sake of creation. They are unable to point to anything prior to creation, except God himself, as an object for which God should act, and are therefore driven to admit (as they clearly must), that God lacked those things for whose attainment he created means, and further that he desired them.

If all things follow from a necessity of the absolutely perfect nature of God, why are there so many imperfections in nature? Such, for instance, as things corrupt to the point of putridity, loathsome deformity, confusion, evil, sin, &c. But these reasoners are, as I have said, easily confuted, for the perfection of things is to be reckoned only from their own nature and power; things are not more or less perfect, according as they delight or offend human senses, or according as they are serviceable or repugnant to mankind. To those who ask why God did not so create all men, that they should be governed only by reason, I give no answer but this: because matter was not lacking to him for the creation of every degree of perfection from highest to lowest; or, more strictly, because the laws of his nature are so vast, as to suffice for the production of everything conceivable by an infinite intelligence.

Spinoza’s metaphysics are beautiful, positive, and perhaps a bit frightening; his Deus siva Natura (God or Nature, whichever helps you dispose of anthropic projections on the supreme cause) is joyfully, infinitely powerful, and does not need a reason to be what he is; he is perfect, and any purpose outside himself for which he would act would only lessen his perfection, bringing him down to our level as beings of deprivation and conflict with other natures. While Spinoza’s God is not troubled by human ends, this is not out of cruelty, but joy. I find this hard but joyful world more blessed than a loving God without power, more agreeable than a powerful God without love, and infinitely more true to the evidence of my senses than a God who is both. But Spinoza is not blind to the difficulty of his way of seeing things. At the end of his ethics, he writes:

If the way which I have pointed out as leading to this result seems exceedingly hard, it may nevertheless be discovered. Needs must it be hard, since it is so seldom found. How would it be possible, if salvation were ready to our hand, and could without great labour be found, that it should be by almost all men neglected? But all things excellent are as difficult as they are rare.

All this is not to say that the crisis of meaning or purpose in modern life is a mere illusion. As Spinoza points out, humans cannot help but be purposeful beings, though we suffer inordinately when we mistakenly believe nature herself to be so oriented. But it is unquestionably true that modernity, since the time of Dostoyevski, Nietzsche, and Marx, has struggled unsuccessfully to answer without possible reversal the question “what purpose should we put ourselves to, as individuals and as societies?” Or: “what is the destiny of Man?”

So with all that necessary preamble, I feel I have circumscribed the real crisis. When conservatives decry nihilism, I believe that in nearly all cases they mean one of the following:

- A feeling that the purpose of human life has lost its immutable, eternal character. Our purpose is now felt to be part of contested history, and this is intolerable.

- A feeling that the stories which once bound people together (religion, progress, etc.) have lost their power to compel belief.

- An objection to decadent (meaning unsustainable, but also generally hedonist) cultural practices.

All three of these problems are projected onto external enemies of real, ordinary Americans, people who generally know without asking what they want and why. Their enemies are always painted with the same broad brushstrokes, though ever with new names:

- Insufferably opaque academics who talk nonsense to feel themselves superior to ordinary people, and who desperately need to indoctrinate the young to prop up their fragile beliefs

- Ugly, perverse men deluded into believing they are women, who need to involve children in their perversity to validate their identities

- Muslims and racialized immigrants who are replacing the white population through affirmative action and free abortions

- Hollywood media moguls and Woke Billionaires, who move the others like pawns on a chessboard, ever closer to their goal of destroying everything simple and decent

The themes above, while constantly seeking a freshly provocative expression, are nothing new; and if we want to avoid falling for their seductive clarity, we must recognize that they never come to us in foreign guises; they come home grown, wearing a skin of familiarity, neighborliness, and patriotism; they come, in short, from us, arising spontaneously anywhere the capitalist mode of production has taken hold. Capitalnote, that wonderful wealth-generating engine which can only operate by replacing what, in centuries past, had been relatively stable orders of production, integrated into social and religious life, with constant technological and social revolution, outstripping our capacity to produce meaning. As Karl Marx put it in The Communist Manifesto:

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form, was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condition of life and his relations with his kind.

In ages past, many human cultures had taken for granted that the world of meaning, symbols, ideas, and cosmic orders produced and determined the world of mere things. The enlightenment, the industrial revolution, and capitalism together made this common and comforting belief difficult to maintain without resorting to conspiratorial narratives. The faster things get, the more these forces compound each other: speed of communication, of travel, of the creation of new commodities, and of algorithms surfacing memes for which we have not yet built up psychic defenses, all combining to make sense making increasingly difficult. And yet, paradoxically, the very conditions which undermine sense making allow for new, partial, unstable forms of narrative construction to thrive: the very conspiracies which were first invented as a refuge from the anxiety of capitalist production take new and frightening vitality from the means of communication built by capital. Ignorance maintained by vast intelligence, poverty maintained by vast wealth.

The Right to Ignorance⌗

Anyone who uses the internet will inevitably find themselves exposed to ideas and practices utterly foreign to themselves, provoking reactions of horror and disgustnote. Due to a confluence of factors, from the need for capitalist economies to forcibly open trade between cultures, to acceleration in the speed of travel and communication, to the unprecedented collapse of language diversity, people are more connected than ever before. The pioneering media theorist Marshall McCluhan, back in the optimistic sixties, predicted that mass media would create a “global village”, in which pain and suffering in one part of the world necessarily elicit the compassion and action of the rest. As everyone knows, this utopian vision didn’t pan out; paradoxically, increased contact is most often used as an opportunity for ingroup reinforcement, using natural gut reactions to the unfamiliar as a powerful catalyst for ideological consolidation, often with violent results. The reasons increased contact does not result in solidarity are many, and may have more to do with the colonization of mass media by the profit motive than the medium itself; but even as conspiratorial thinking thrives both online and in traditional mass media, conservatives constantly decry censorship and demand their ideas carry more respect. While explicit censorship of conservatives (along with all sorts of fringe ideas opposed to the liberal hegemony) certainly exist, it’s worth pointing out that the this is not entirely the result of a conspiracy, but is an inevitable result of the dynamics of instant communication. Beyond a certain point, having in-depth knowledge of every possible human practice is incompatible with the conviction at the root of all conservatism: that your own form of existence is the only acceptable form; or, at least that it is beyond rational challenge. To truly maintain this belief, you must either forcibly close the floodgates, or, without realizing it, slide into a sort of cosmopolitanism, albeit one of constant opposition.

The sort of conservatives who constantly remind us that they are and want to be a part of the discourse are, then, a seeming contradiction. Which is why I make an important distinction between systematic rejections of modernity (like the Amish, who have plenty of serious issues of their own), and what people like Matt McManus have taken to calling postmodern conservatism, a movement which is thoroughly embedded in and defined by the problems of a modernity it claims to reject. Most conservatives claim to be committed to classical liberal values like free speech, democracy, the marketplace of ideas, and Reals over Feels. But in the last several generations, conservativism has been losing share in that cherished marketplace of ideas, especially among the young. It seems the values conservatives are putting forward are, on their own merits, unappealing to most people who are just trying to make it in modern societies, including their own children. Given this, it is inevitable that conservatives will find a way to distort or abandon the liberal values which are not producing the outcomes they want. To justify their contortions, conservatives employ totalizing narratives that allow them to scapegoat their own actions on others who have an unfair advantage. Some examples:

- The democratic process is illegitimate and untrustworthy. Democrats are cheating with fake votes, and buying votes from people who are not Real Americans. Under these circumstances, it is impossible for us to win fairly. Since they are not fighting fair, we don’t have to either.

- Parents have the absolute right to decide what their children learn and who they associate with. Anyone who attempts to teach children a way of understanding the world their parents do not expressly consent to is an abuser. Because they are abusive, we are entitled to use the state and private vigilantism to silence them.

- In a world with genuine free speech, conservative ideas would be respectable in the public discourse. If conservative ideas are excluded or not respected on mainstream communication platforms, this cannot be the result of individuals exercising their first amendment right to exclude speech they dislikenote; it must constitute illegitimate censorship.

- Most higher education institutions lean liberal. This must be an artificial result created by certain individuals in pursuit of power and money. We are committed to Truth, but educated people are for the most part corrupted by an illegitimate outside influence. Therefore, education and credentialism should be viewed with suspicion, unless they are explicitly grounded in conservative principles.

All these narratives cover over what seems, if you take a longer view than conservatives usually do, to be built-in tendency of modernity, and of the classical liberal values that postmodern conservatives claim to be committed to. Modernity is liberalizing. If you enjoy the benefits of free thought and market competition, you also inevitably open the doors to all sorts of degenerate cosmopolitanism. To resolve this conflict, conservatives invent a menagerie of villains out to destroy the Christian way of life, motivated by a combination of profit and pure pleasure in destruction. These enemies, in turn, grant them permission to selectively abandon liberal principles, in order to save them.

But I would contend that conservatives who participate in modern societies, regardless of their explicit beliefs about God, are already halfway to atheists in all the ways that matter; and further, they know it, at least unconsciously, and the anxiety it engenders is why postmodern conservatives make such a constant (and highly profitable) racket about nihilism.

Who is an atheist?⌗

Sigmund Freud diagnosed the crisis engendered by modernity as the result of three great “outrages” brought on by the sciences:

Humanity has in the course of time had to endure from the hands of science two great outrages upon its naive self-love. The first was when it realized that our earth was not the center of the universe, but only a tiny speck in a world-system of a magnitude hardly conceivable; this is associated in our minds with the name of Copernicus, although Alexandrian doctrines taught something very similar. The second was when biological research robbed man of his peculiar privilege of having been specially created, and relegated him to a descent from the animal world, implying an ineradicable animal nature in him: this transvaluation has been accomplished in our own time upon the instigation of Charles Darwin, Wallace, and their predecessors, and not without the most violent opposition from their contemporaries. But man’s craving for grandiosity is now suffering the third and most bitter blow from present-day psychological research which is endeavoring to prove to the ego of each one of us that he is not even master in his own house, but that he must remain content with the veriest scraps of information about what is going on unconsciously in his own mind.

Humans have long enjoyed the unselfconscious privilege of telling stories that place them at the center of everything. While this way of looking at things can and does arise spontaneously in many cultures, it is particularly dogmatic in western thought. The world is the creation of a God with human-like qualities, who made the world in order to place his most special and God-like creation, Man, in charge of it. Originally, everything existed for Man’s use and enjoyment. It was an aberration, a fault, sin, that made it so that we often come into violent conflict with nature. While Galileo did not come up with the theory of heliocentrism, his conflict with the church demonstrates how long-established scientific theories can come into sudden and violent conflict with the way a human culture subconsciously sees itself, and how hard it is to change those subconscious ideas once established, evidence be damned.

One can view modernity as a series of repetitions of one of three basic solutions to the crisis of humanity’s humiliation by its own inquiry:

The Evangelical Solution: Deny it⌗

Another example of a violent clash between empirical science and society’s unconscious beliefs is the American Evangelical movement’s rejection of evolution and the ancient earth in the twentieth century. To some, if the human history we know turns out to be only a tiny fraction of the history of human life, let alone life on earth, let alone the universe, it can’t help but undermine the notion of earth as the stage for God’s story through Man. But the people who first peered into the abyss of Deep Time assigned it a very different meaning, which spoke to them of the glory and majesty of God.

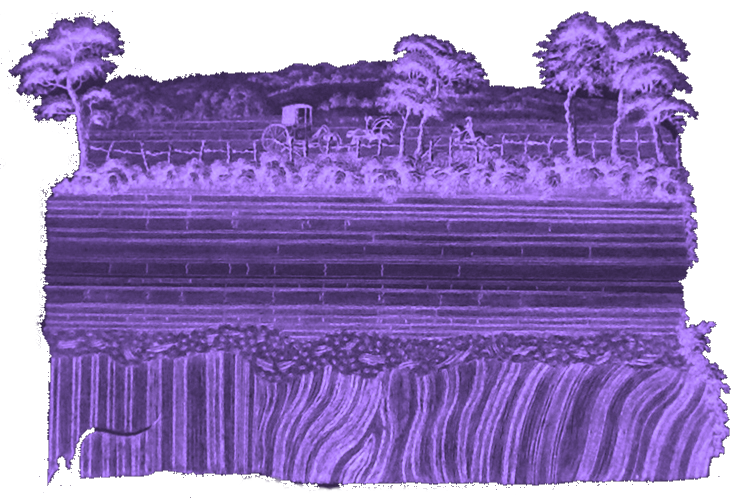

One such early proponent of an ancient earth was James Hutton, who published his masterwork Theory of the Earth in 1795, nearly a century before Darwin published On the Origin of the Species. Generally considered to be an impenetrable mess, his theories were popularized by his fiend John Playfair, who remarked: “On those of us who saw these phenomena for the first time, the impression made will not easily be forgotten… The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time.” What made such an impression on Hutton and his friends was a geological feature he called an unconformity.

As the late Stephen Jay Gould explains in his brilliant and accessible Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle, an unconformity is

…a fossil surface of erosion, a gap in time separating two episodes in the formation of rocks. Unconformities are direct evidence that the history of our earth includes several cycles of deposition and uplift…Since large expanses of water-laid strata must be deposited flat (or nearly so), the underlying vertical sequence arose at right angles to its current orientation. These strata were then broken, uplifted, and tilted to vertical in forming land above the ocean’s surface. The land eroded, producing the uneven horizontal surface of the unconformity itself. Eventually, the seas rose again (or the land foundered) and waves further planed the old surface, producing a “pudding stone” of pebbles made from the vertical strata. Under the sea again, horizontal strata formed as products of the second cycle. Another period of uplift then raised these rocks above the sea once more, this time not breaking or tilting the strata…Thus, we see in this simple geometry of horizontal above vertical two great cycles of sedimentation with two episodes of uplift.

It was evidence of this kind which undermined the theory that the sedimentation we observe could be the result of a single catastrophic event, such as a global flood. Unconformities evidence two distinct periods of gradual deposit; even assuming sedimentation faster than any we’ve observed, the minimum time for such a sequence is far longer than the oldest recorded histories.

It is often hard, when trying to understand phenomena involving quantities in the billions, to feel intensely what such enormity really means. Which is why connecting deep time to the specific geological features which first awakened people to the vastness of time works better than talking only in numbers. Contemplating the enormous expanse of time captured in the illustration above fills me with sublime awe. Hiking in Great Falls, Virginia, walking over layers of rock laid by centuries of slow deposit at the bottom of an ocean, then turned ninety degrees by an unimaginably forceful event, I feel the uncanny presence of a vastness I can never hope to comprehend.

It might be easy to mistake this giddiness for a thoroughly modern glee in iconoclasm. We often depict the history of scientific progress as an ideological struggle between iconoclasts and traditionalists. We project onto the men and women behind mankind’s great dethronements a certain illicit pleasure in humbling God and, through him, Man. Unquestionably, many have such inclinations, and I would be dishonest if did not admit a certain joy in iconoclasm myself. But Hutton, on the contrary, saw the vastness of time as evidence that the earth had been made by God in specific accord with human nature: “a world contrived in consummate wisdom for the growth and habitation of a great diversity of plants and animals; and a world peculiarly adapted to the purpose of man, who inhabits all its climates, who measures its extent, and determines its productions at his pleasure.”

The history of naturalism from the 17th century up through Darwin is littered with such examples: god-fearing men who, despite their explicit commitment Christianity and unconscious acceptance of the anthropocentric world picture, nevertheless carefully laid each stone on the path that leads to a world largely indifferent to human essence and destinycite. The vastness of time came gradually to light in spite of the preconceptions of the people who discovered it. It was not, as we often imagine, a conscious desire to challenge God’s authority, which sought empirical justification. Just the opposite; iconoclasts vs traditionalists is an attempt to project back onto history a narrative which serves contemporary ideological objectives, for both Christians and secularists.

As the 20th century progressed, long after deep time and evolution had been fully sedimented (heh) in the sciences, more and more conservative evangelicals began to adopt a hard-line, Biblical literalist approach to anything smelling like evolutionism. It’s critical to realize, however, how lately this reaction was completed. Even into the 1920s, evolution was not widely considered incompatible with Christianity, even among Fundamentalists:

‘Fundamentalism’ takes its name from a series of articles defending traditional Christianity against the liberalness of scholarly ‘higher criticism’ of the Bible text, in which scholars concluded that the Bible was a very human product of centuries of editing and redacting. The articles were collectively entitled The Fundamentals, and were originally published between 1910 and 1915 by the Bible Institute of Los Angeles (BIOLA) (The Fundamentals were edited in part by conservative apologist R. A. Torrey [1856–1928], the founder of BIOLA, who also edited the Institute’s journal, The King’s Business.)…Interestingly, early ‘fundamentalism’ does not appear to have been as anti-evolutionary as the later movement. Noll has noted that the editors and authors of The Fundamentals were comfortable with an ancient Earth, and that even leading Fundamentals writers, such as Scottish Presbyterian James Orr and American Presbyterian B. B. Warfield (who occupied the Charles Hodge Chair at the then-conservative Princeton Theological Seminary), ‘allowed for large-scale evolution in order to explain God’s way of creating plants, animals, and even the human body’ (Noll 1994). However, the authors always put some limit on evolution. For example, Orr still invoked divine intervention to account for the origin of life and of human consciousness. He also put significant faith in the idea that the ’eclipse’ of Darwin’s gradualist, selectionist version of evolution was an indication that science would permanently move towards more teleology-friendly theories (Orr 1910–1915a, 1910– 1915b, 1910–1915c).cite

Popular anti-evolutionism briefly surged in the twenties, thanks to campaigning by William Jennings Bryan, who managed to get the theory banned in several states. His campaign came to a head in the much-publicized and now infamous Scopes Monkey Trial, in which Bryan successfully convicted a high school teacher of violating the prohibition. Unable to convince the judge to make the validity of the law at issue in the case, the defense, led by the prominent agnostic Clarence Darrow, instead took advantage of the media spectacle and goaded Bryan into taking the stand in defense of Fundamentalism itself. Darrow proceeded to thoroughly embarrass Bryan, and with him Fundamentalism, at least in the eyes of the popular press. For some decades after this, fundamentalism retreated from public scrutiny, until the advent of mass media made it possible to combine many strains of popular fundamentalism into a single movement with money and political influence, forming what is today called Evangelicalism.

Although conservative evangelicals continued to view evolution with suspicion, it wasn’t until Henry Morris and John Whitcomb’s 1961 The Genesis Flood that evangelicals fully consolidated around Young Earth Creationism as their bulwark against liberalizing tendencies. Before that time, it was common among evangelicals to interpret Genesis via the Gap Theory or Day Age Theory, each of which provided different accommodations for an ancient earth without sacrificing Biblical inerrancy. But the Young Earth Creationists, deciding this was giving dethronement a foot in the door, and able to leverage the might of a large and coordinated media empire, pushed the evangelical movement toward a set of strategic doctrines blatantly at odds with natural history, the better to insulate it from Darwin.

However, it turns out to be difficult for moderns, even die-hard Fundamentalists, to fully escape the anxieties engendered by man’s dethronements. Even if one consciously refuses it, the fault runs so deep through the modern world that it’s almost impossible to unconsciously live in a Neoplatonist universe, in deep and eternal spiritual accord with human nature and destiny. It is easy to miss that we are much closer to our contemporary “opposite” in our preconscious way of seeing the world than we are to the most liberal person alive in the sixteenth centurynote (for example, from a Neoplatonist perspective, it was literally inconceivable that species could go extinct, a stumbling block in the study of fossils for centuries.) However you consciously identify, by living in a technological world made possible by massive advances in human knowledge, you are constantly and subconsciously agitated by an alternative cosmology in which humans are not the center of reality, and in which our little world of meaning comes to be within and after a reality which vastly exceeds it.

However, science does not wait for the subconscious views of all or even most people to catch up to its findings. Since we lack an alternative mythology to replace the old one (and since what wins in a marketplace of ideas is not necessarily Truth, but beliefs which enable the right behaviors), most if not all of us rarely see the world in fully non-anthropocentric terms either (this is closely linked to our inability to see and react to the current ecological crisis). In Full House: The Spread of Excellence From Plato to Darwin, Gould demonstrates how anthropocentric notions slip even into common understandings of evolutionary history:

My favorite example of unrecognized bias in depicting the history of life resides quite literally in the pictures we paint. We all know these series of paintings–from a first scene of trilobites in the Cambrian sea, through lots of dinosaurs in the middle, to a last picture of Cro-Magnon ancestors busy decorating a cave in France. We have viewed these sequences on the walls of natural history museums, and in coffee-table books about the history of life…what could be wrong about such a series? Trilobites did dominate the first faunas of multicellular organisms; humans did arise only yesterday; and dinosaurs did flourish in between. Why am I complaining?

The paintings are ‘right’ in a narrow sense. But nothing can be more misleading than formally correct but limited information drastically yanked out of context. (Remember the old story about the captain who disliked his first mate and recorded in the ship’s log, after a unique episode, ‘First mate was drunk today.’ The mate begged the captain to remove the passage, stating correctly that this had never happened before and that his employment would be jeopardized. The captain refused. The mate kept the next day’s log, and he recorded, ‘Captain was sober today.’)

As for this nautical tale, so for the history of life. All the prominent paintings in this genre of prehistoric art claim to be portraying the nub or essence of life’s history through time. They all begin with a scene or two of Paleozoic invertebrates. We note our first bias even here, for the prevertebrate seas span nearly half the history of multicellular animal life, yet never commandeer more than 10 percent of the pictures. As soon as fishes begin to prosper in the Devonian period, underwater scenes switch to these first vertebrates–and we never see another invertebrate again for all the rest of the pageant. Even the fishes get short shrift, for not a single one ever appears again (except as fleeing prey for an ichthyosaur or a mosauar) after the emergence of the terrestrial vertebrate life toward the end of the Paleozoic era…Invertebrates didn’t die or stop evolving after fishes appeared; much of their most important history unrolls in contemporaneous partnership with marine vertebrates…Similarly, fishes didn’t die out or stop evolving just because one lineage of peripheral brethren managed to colonize the land.

Let me not carp unfairly. If these pageantries only claimed to be illustrating the ancestry of our tiny human twig on life’s tree, then I would not complain, for I cannot quarrel unduly with such a parochial decision, stated up front. But these iconographic sequences always purport to be illustrating the history of life, not a tale of a twig…Much as we may love ourselves, Homo sapiens is not representative, or symbolic, of life as a whole. We are not surrogates for arthropods (more than 80% of animal species), or exemplars of anything either particular or typical. We are the possessors of one extraordinary evolutionary investment called consciousness–the factor that permits us, rather than any other species, to ruminate about such matters (or, rather, cows ruminate and we cogitate). But how can this invention be viewed as the distillation of life’s primary thrust or direction when 80 percent of multicellularity enjoys such evolutionary success and displays no trend to neurological complexity through time–and when our own neural elaboration may just as well end up destroying us as sparking a move to any other state that we would choose to designate as ‘higher’?

In light of our new (compared to most humans through time) self-understanding, Gould suggests we “trade the traditional source of human solace in separation for a more interesting view of life in union with other creatures, as one contingent element of a much larger history. We must give up a conventional notion of human domination, but we learn to cherish particulars, of which we are but one, and to revel in the complete ranges, to which we contribute one precious point–a good swap, I would argue, of stale (and false) comfort for broader understanding.”

Contrast the atheism of Gould with that of Stephen Pinker or Richard Dawkins, who explicitly deny the existence of God, but still speak as if God’s command to Adam and Eve to “fill the earth and subdue it” is in full effect. Theirs is another answer to the problem of how to deal with the death of God:

The Humanist Solution: Ignore It⌗

Between believers and non-believers, there is only a razor’s edge; on both sides of the razor, the abyss of willful ignorance.

From the ashes of God’s demise, a simple solution rises: put Man in his place. Instead of the Natural and the Good being given to Man by God, the Natural and the Good will be given by Man to themselves, in accordance with their own eternal nature. This is the thrust of many currents of enlightenment rationalism. This much Christian conservatives perceive and decry. What they react to is the audacity of humanity determining their own ends. How, given our fallibility, our depravity, how dimly we see, can we make our own destiny? And indeed, from a certain perspective, it seems modernity is an endless accumulation of humanity’s failures to legislate themselves. But what conservatives fail to see is that the Secular Humanists are but the other side of the coin of Christianity. Nietzsche’s idea of the Death of God is our retroactive realization that we were always, in reality, legislating ourselves, whether we did so consciously and in our own name, or whether we attribute Nature to a separate being in our image. Whether believer or atheist, the thing that matters is whether you still see the world in anthropocentric terms. God or Man, depraved or perfectible, both flatter our vanity, blinding us to our responsibility to and interconnection with the rest of life on earth.

But there’s a deeper problem with simply swapping the concept “God” with “Man” that goes beyond simple hubris. As Friedrich Nietzsche convincingly argued, the speed of progress in modernity awoke humanity to an even more destabilizing notion than undermining our belief in a rational God. The American constitution’s most important founding principle is the belief that humans are endowed by God with “certain, inalienable rights”. Underlying this belief is a notion that the nature of human beings, their basic needs, desires, what is good and bad, healthy and poisonous to them, are eternal and preordained. One of the ways the term Humanism is used is to designate this notion, deeply embedded in classical liberalism. While human societies may always involve a certain amount of conflict, in theory a “least imperfect” form of society exists, since there is but one, eternal human nature. While we do not always know what we should do, and we often fail even when we do know, we can rest assured that the standard is always there, always given, and we have only to uncover it and conform to it. In the past, Nietzsche argues, this “illusion” never came to consciousness because the speed at which humanity changed was so slow, it couldn’t be perceived in one lifetime. But as the speed at which our technologies, and with them, our ideas, change increased massively with the enlightenment and the industrial revolution, it came to the attention of at least some of the human race that, rather than being eternally fixed, our nature had always been involved in a contested process of struggle between multiple possibilities, an ever-renewed process of Becoming. With the idea that, rather than having an eternal essence, we were always in the process of becoming something new, God and Man were struck down in one stroke:

No one gives man his qualities, neither God, society, his parents, his ancestors, nor himself (—this non-sensical idea which is at last refuted here, was taught as “intelligible freedom” by Kant, and perhaps even as early as Plato himself). No one is responsible for the fact that he exists at all, that he is constituted as he is, and that he happens to be in certain circumstances and in a particular environment. The fatality of his being cannot be divorced from the fatality of all that which has been and will be. This is not the result of an individual intention, of a will, of an aim, there is no attempt at attaining to any “ideal man,” or “ideal happiness” or “ideal morality” with him,—it is absurd to wish him to be careering towards some sort of purpose. We invented the concept “purpose”; in reality purpose is altogether lacking. One is necessary, one is a piece of fate, one belongs to the whole, one is in the whole,—there is nothing that could judge, measure, compare, and condemn our existence, for that would mean judging, measuring, comparing and condemning the whole. But there is nothing outside the whole! The fact that no one shall any longer be made responsible, that the nature of existence may not be traced to a causa prima, that the world is an entity neither as a sensorium nor as a spirit—this alone is the great deliverance,—thus alone is the innocence of Becoming restored…. The concept “God” has been the greatest objection to existence hitherto…. We deny God, we deny responsibility in God: thus alone do we save the world.cite

Rather than yearn for a return to certainty and bondage, Nietzsche argues, our only, happy choice, is to accept that we are profoundly, inescapably free. It may be that the giddiness you feel at the prospect of Becoming dwarfs the already overwhelming vertigo provoked by those other dethronements. What if we become the wrong thing? From a certain perspective, the infinite debt doesn’t seem so bad; at least we know what the rules are, even if we can never hope to live up to them. Perhaps this feeling of vertigo at our unbearable freedom is why Humanism and Being are the implicit premise in liberal societies. As Marx, who himself at times comes off like a humanist, observed, capitalism, together with the scientific revolution bound up with it, tends to destabilize our belief in a fixed, eternal essence of Man. The conflict between, on the one hand, belief in fixed human nature, and on the other the fact of perpetual economic and cultural revolution, is the cause of the modern anxiety which we use stories of an evil Other to assuage. Both liberalism and conservatism need fixed human nature for their ideologies to have consistency. But Marx was wrong. No society ever died of its contradictions. On the contrary, contradictions are the engines which spur societies ever onward. The contradiction between humanism and the tendency of liberal societies to revolutionize how we live and think is exactly this sort of engine, and it is driving us absolutely mad.

The Post Humanist Solution: Change our world picture⌗

While it should be obvious by now this is the solution I prefer, I confess it is nearly impossible to achieve on a large scale. Subconscious models of the world don’t need to be true to motivate behavior, and they don’t necessarily respond to reasoning. At times, it feels like the modern world is implicitly atheist; whether you believe in God or not, moderns, including conservatives, don’t seem to see the world as place rationally organized in accord with human happiness. But at other times, it feels like the old anthropocentric model is alive and well. Modernity is in large part defined by this double vision, this inability to lock in a clear idea of our relationship to the world and its meaning.

The problem of man’s destiny is as old as modernity itself. What defines postmodernity, for thinkers like Jean-François Lyotard, is just this sort of double vision: it’s not just that we don’t believe in the story of Man, but that we don’t believe in any totalizing story about reality at all. As individuals, we alternate between indifference and anxiety; while our societies increasingly tend to measure everything by the same criteria: does it work? Or more precisely: is it profitable?

Science has always been in conflict with narratives. Judged by the yardstick of science, the majority of them prove to be fables. But to the extent that science does not restrict itself to stating useful regularities and seeks the truth, it is obliged to legitimate the rules of its own game. It then produces a discourse of legitimation with respect to its own status, a discourse called philosophy. I will use the term modern to designate any science that legitimates itself with reference to a metadiscourse of this kind making an explicit appeal to some grand narrative, such as the dialectics of Spirit, the hermeneutics of meaning, the emancipation of the rational or working subject, or the creation of wealth. For example, the rule of consensus between the sender and addressee of a statement with truth-value is deemed acceptable if it is cast in terms of a possible unanimity between rational minds: this is the Enlightenment narrative, in which the hero of knowledge works toward a good ethico-political end–universal peace. As can be seen from this example, if a metanarrative implying a philosophy of history is used to legitimate knowledge, questions are raised concerning the validity of the institutions governing the social bond: these must be legitimated as well. Thus justice is consigned to the grand narrative in the same way as truth.

Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodem as incredulity toward metanarratives. This incredulity is undoubtedly a product of progress in the sciences: but that progress in turn presupposes it. To the obsolescence of the metanarrative apparatus of legitimation corresponds; most notably, the crisis of metaphysical philosophy and of the university institution which in the past relied on it. The narrative function is losing it functors, its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal. It is being dispersed in clouds of narrative language elements–narrative, but also denotative, prescriptive, descriptive, and so on. Conveyed within each cloud are pragmatic valencies specific to its kind. Each of us lives at the intersection of many of these. However, we do not necessarily establish stable language combinations, and the properties of the ones we do establish are not necessarily communicable.

Thus the society of the future falls less within the province of a Newtonian anthropology (such as stucturalism or systems theory) than a pragmatics of language particles. There are many different language games-a heterogeneity of elements. They only give rise to institutions in patches-local determinism.

The decision makers, however, attempt to manage these clouds of sociality according to input/output matrices, following a logic which implies that their elements are commensurable and that the whole is determinable. They allocate our lives for the growth of power. In matters of social justice and of scientific truth alike, the legitimation I of that power is based on its optimizing the system’s performance–efficiency. The application of this criterion to all of our games necessarily entails a certain level of terror, whether soft or hard: be operational (that is, commensurable) or disappear. The logic of maximum performance is no doubt inconsistent in many ways, particularly with respect to contradiction in the socio-economic field: it demands both less work (to lower production costs) and more (to lessen the social burden of the idle population). But our incredulity is now such that we no longer expect salvation to rise from these inconsistencies, as did Marx.cite

Of Aristotle’s four causes, empiricism turns out to make productive use of only one, efficient cause. Due to the enormous success of this approach in increasing total wealth, over the course of the modern era we’ve tended to view final cause (let alone formal cause, a way of seeing almost incomprehensible to moderns) as something increasingly epiphenomenal and psychological; it gives structure and clarity to the lives of conscious beings, but little else. Another crushing blow to the vanity of purposive beings. As this way of seeing things gains ground, it becomes difficult to see even our own societies as anything other than machines for managing threats to their own existence, indifferent to any mere human values or ends, and having an eye only toward efficiency. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the defeat of communism, we passed from a time when alternative narratives competed to define the meaning of history, into an era in which no one really believes history has a meaning. As Margaret Thatcher put it: “[S]ociety? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families”. Those who somehow haven’t got the message yet, still clinging to outdated narratives like The Class Struggle seem comically credulous and out of touch. We spend more time arguing and telling stories than ever, but none of them seem to take hold of us; yet we hunger for them all the more. It is in this sense that I talk about postmodern conservatism; fixated on culture wars, lacking a concrete political program, and only capable of telling a totalizing story negatively via endless external threats to a society which does not exist.

But it is not just conservatism; our politics, left and right, seem dominated by this frenzied stasis, all the more metastable the more it keeps us in a state of constant excitation and exhaustion. Whether the story is god’s final judgment or the historical inevitability of communism, the question is the same: can we will ourselves back into believing in a lost totality, a transcendent destiny? When conservatives, secular or Christian, discuss postmodernism, they often scapegoat the phenomenon on the very academics describing it (Jacques Derrida and Jean Baudrillard being favored targets), with purported motives ranging from mere obscurantism to a megalomaniacal obsession with undermining Truth. As I hope I’ve demonstrated by now, if anything can be described as nihilism, it is the stubborn insistence on beliefs not because they are true, but because they are good for society. Most importantly, because it can never work. A lie, even a useful one, believed out of duty or guilt becomes something different than what it was when believed out of sincere ignorance: a dangerous, unstable farce, tinged with resentment. I can think of no better description of postmodern conservatism, a movement which, far from being a threat to the postmodern condition, seems only to reinforce it with its constant demands to restore a common language, a common sense. Look at, on the one hand, the constant demand from conservatives to restore a single totalizing narrative, always alluded to in vague terms like traditional values, and on the other the way they mock liberals for being so behind the times as to expect everyone unironically “trust the science” and buy into backward metanarratives like “scientific consensus”. Lyotard’s analysis has so much explanatory power for seemingly contradictory phenomena like Evangelicals backing Trump, a man personally and, until recently, politically the apparent opposite of Evangelicalism. They have simply caught up to the rules of postmodernity: interiority, consistency, even the past, none of it matters. The content of utterances are irrelevant, only whether they agitate the right systems in the right ways, all in pursuit of raw power. Yet postmodern conservatives, except for a few savvy operatives who consciously embrace this nihilistic, functionalist approach to politics, get to enjoy a conscious (though unstable) consistency through projection and scapegoating. In the postmodern world, but not of it.

I cannot pretend I am immune to this dynamic, this development (or degeneration) of our profound freedom, nor do I think its effects are entirely negative. Lyotard, far from being against postmodernity, points out the “severe reexamination which postmodernity imposes on the thought of the Enlightenment, on the idea of a unitary end of history and of a subject”, an “illusion” which can only be maintained through “terror”:

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries have given us as much terror as we can take. We have paid a high enough price for the nostalgia of the whole and the one, for the reconciliation of the concept and the sensible, of the transparent and the communicable experience. Under the general demand for slackening and for appeasement, we can hear the mutterings of the desire for a return of terror, for the realization of the fantasy to seize reality. The answer is: Let us wage a war on totality; let us be witness to the unpresentable; let us activate the differences and save the honor of the name.

What might this “war on totality” look like? Isn’t this really just quietism? Should I resign myself to being swept along by the perpetual revolution machine of capitalism? No plan, no vision for the future, just doomed to freely and endlessly remix an increasingly degenerated cultural soup into my own personal “motley painting of everything that has ever been believed”? Not at all. But to even begin to challenge our present condition, we must recognize that the ever accelerating catastrophe is not remotely threatened by our demands to restore totality; it thrives on it. Maybe a rejection of nihilism requires we acknowledge a certain split, an instability at the root of the human subject, which has been made undeniable by postmodernity, and to stop pretending to an illusory wholeness. It is difficult to build a politics which is not premised on human nature, rights, and an illusory common cause, but it is necessary. Nor do I believe it confine us to passivity or austerity; but it does require us to do a lot of difficult work to build solidarity with people and practices that perplex and disgust us.

In their heady and impenetrable critical work Anti-Oedipus, Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari describe two “poles” of the tendency of capitalism to erode stable cultures and beliefs in order to make everything codeable and saleable by the system: the leading edge of the tendency they call the “schizophrenic” or “revolutionary” pole; the reactions to it they call “paranoiac” or “fascistic”. While obviously these labels carry implicit value judgments, it’s important to understand that they aren’t simply saying we should give up, thoughtlessly embrace constant revolution, and gleefully destroy our every comforting illusion (which they call deterritorialization.) In fact, what they argue is that everyone, except the clinically insane, can’t help but create islands of intelligibility and stability (reterritorializations), temporarily interrupting the process which is forcing everything to talk in the same language, money. They describe the subjective and objective world as a single metaphysical tendency, in order to explore the complex ways in which economies produce subjectivities produce economies to infinity; and to show how this endless, chaotic vertigo tends to undermine our belief in the real at all, retreating into to the mere freedom to endlessly reshape our subjectivity (termed Oedipalization, the individualization, psychologization, and medicalization of the anxiety inevitably produced by modernity.) At times, both liberals and conservatives embrace and enjoy the revolutionary frenzy which is always in the air (it’s from this perspective that one can make sense of a conservative movement which describes itself at once as “traditional” and “radical”); at other times, they adopt the role of cop or Superego, wringing hands at the other side’s heedless embrace of destruction and inconsistency. Rather than willing ourselves back into undead totalities like God, Man, or the universal subject of history, the Proletariat, perhaps the way of freedom lies, paradoxically, in “fleeing”:

To those who say that escaping is not courageous, we answer: what is not escape and social investment at the same time? The choice is between one of two poles, the paranoiac counterescape that motivates all the conformist, reactionary, and fascisizing investments, and the schizophrenic escape convertible into a revolutionary investment. Maurice Blanchot speaks admirably of this revolutionary escape, this fall that must be thought and carried out as the most positive of events: ‘What is this escape? The word is poorly chosen to please. Courage consists, however, in agreeing to flee rather than live tranquilly and hypocritically in false refuges. Values, morals, homelands, religions, and these private certitudes that our vanity and our complacency bestow generously on us, have as many deceptive sojourns as the world arranges for those who think they are standing straight and at ease, among stable things. They know nothing of this immense flight that transports them, ignorant of themselves, in the monotonous buzzing of their ever quickening steps that lead them impersonally in a great immobile movement. An escape in advance of the escape. [Consider the example of one of these men] who, having had the revelation of the mysterious drift, is no longer able to stand living in the false pretenses of residence. First he tries to take this movement as his own. He would like to personally withdraw. He lives on the fringe… [But] perhaps that is what the fall is, that it can no longer be a personal destiny, but the common lot.’

Modernity forces on us certain sober realities, which we cannot fully push out of sight without resorting to racist conspiracy theories: our material reality sets the boundaries for the meanings we can assign reality, not the other way around; there is not one right way to be a human, there is not just one name by which you may be saved; that a certain type of wholeness and eternity have been lost to us, but with this loss we discover a freedom to remake ourselves and our concepts, to imagine new ways to relate to ourselves, our communities, and nature. Donna Haraway in The Cyborg Manifesto advocates we learn to embrace and enjoy both the freedom and responsibility of being an unstable, interdependent subject, who’s edges bleed out into the whole field of human, animal, social, and machinic:

The cyborg is resolutely committed to partiality, irony, intimacy, and perversity. It is oppositional, utopian, and completely without innocence….The relationships for forming wholes from parts, including those of polarity and hierarchical domination, are at issue in the cyborg world. Unlike the hopes of Frankenstein’s monster, the cyborg does not expect its father to save it through a restoration of the garden—that is, through the fabrication of a heterosexual mate, through its completion in a finished whole, a city and cosmos. The cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the organic family, this time without the oedipal project. The cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust. Perhaps that is why I want to see if cyborgs can subvert the apocalypse of returning to nuclear dust in the manic compulsion to name the Enemy. Cyborgs are not reverent; they do not re-member the cosmos. They are wary of holism, but needy for connection—they seem to have a natural feel for united-front politics, but without the vanguard party….From the perspective of cyborgs, freed of the need to ground politics in “our” privileged position of the oppression that incorporates all other dominations, the innocence of the merely violated, the ground of those closer to nature, we can see powerful possibilities. Feminisms and Marxisms have run aground on Western epistemological imperatives to construct a revolutionary subject from the perspective of a hierarchy of oppressions and/or a latent position of moral superiority, innocence, and greater closeness to nature. With no available original dream of a common language or original symbiosis promising protection from hostile “masculine” separation, but written into the play of a text that has no finally privileged reading or salvation history, to recognize “oneself” as fully implicated in the world, frees us of the need to root politics in identification, vanguard parties, purity, and mothering. Stripped of identity, the “bastard” race teaches about the power of the margins and the importance of a mother like Malinche. Women of color have transformed her from the evil mother of masculinist fear into the originally literate mother who teaches survival…Taking responsibility for the social relations of science and technology means refusing an anti-science metaphysics, a demonology of technology, and so means embracing the skillful task of reconstructing the boundaries of daily life, in partial connection with others, in communication with all of our parts. It is not just that science and technology are possible means of great human satisfaction, as well as a matrix of complex dominations. Cyborg imagery can suggest a way out of the maze of dualisms in which we have explained our bodies and our tools to ourselves. This is a dream not of a common language, but of a powerful infidel heteroglossia. It is an imagination of a feminist speaking in tongues to strike fear into the circuits of the supersavers of the new right. It means both building and destroying machines, identities, categories, relationships, space stories. Though both are bound in the spiral dance, I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess.

All sorts of questions and difficulties remain. But this much I know: we cannot overcome the feeling of strangeness, of time out of joint, of spinning out into the void simply by guilting ourselves into a false and unstable pretense of unity and coherence; it can only result in a resentful lie, in fascism. Nor can we, as mere fallible beings who need a bit of stability and identity to function, throw ourselves heedlessly into the process uniting the human and the inhumannote, free of responsibility for the shape our lives and our societies take. I acknowledge that the middle way, not entirely guilty nor completely innocent, the way of jurisprudence is exceedingly hard. It is not equally open to all, and it will never be a straightforward path to power, security, and ease. But a rejection of nihilism means, most basically, that we abandon the dreams which served other peoples in other times, and begin to make our own, better adapted to the moment we find ourselves in. By giving up our demand for rootedness, a demand which can at present only be fulfilled through terror, we find ourselves open to movement, play, and solidarity; to a politics beyond the racism of universalist myths and perfect evils.

-

“Let us state what, i.e. what kind of thing, substance should be said to be, taking once more another starting-point; for perhaps from this we shall get a clear view also of that substance which exists apart from sensible substances. Since, then, substance is a principle and a cause, let us pursue it from this starting-point. The ‘why’ is always sought in this form–‘why does one thing attach to some other?’ For to inquire why the musical man is a musical man, is either to inquire–as we have said why the man is musical, or it is something else. Now ‘why a thing is itself’ is a meaningless inquiry (for (to give meaning to the question ‘why’) the fact or the existence of the thing must already be evident-e.g. that the moon is eclipsed-but the fact that a thing is itself is the single reason and the single cause to be given in answer to all such questions as why the man is man, or the musician musical’, unless one were to answer ‘because each thing is inseparable from itself, and its being one just meant this’; this, however, is common to all things and is a short and easy way with the question). But we can inquire why man is an animal of such and such a nature. This, then, is plain, that we are not inquiring why he who is a man is a man. We are inquiring, then, why something is predicable of something (that it is predicable must be clear; for if not, the inquiry is an inquiry into nothing). E.g. why does it thunder? This is the same as ‘why is sound produced in the clouds?’ Thus the inquiry is about the predication of one thing of another. And why are these things, i.e. bricks and stones, a house? Plainly we are seeking the cause. And this is the essence (to speak abstractly), which in some cases is the end, e.g. perhaps in the case of a house or a bed, and in some cases is the first mover; for this also is a cause. But while the efficient cause is sought in the case of genesis and destruction, the final cause is sought in the case of being also.” Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book VII

-

One recent example of the conflict between the doctrine of sola scriptura and the real world influence of ideas outside the text is in the recent coup attempted by conservative evangelicals at the Southern Baptist Convention. The fight was started over a 2019 resolution on Critical Race Theory, which describes it as “a set of analytical tools that explain how race has and continues to function in society” which has been “appropriated by individuals with worldviews that are contrary to the Christian faith, resulting in ideologies and methods that contradict Scripture”, and while believers can derive “selective insights” from the theory, it “should only be employed as analytical tools subordinate to Scripture”. This was, in the minds of evangelicals who need to believe their ideas have never fundamentally changed, cause for total war.

-